Condo Case Law Summary: Special Assessments – They Suck, but Pay Them.

Every once in a while, it’s nice to see a little reminder about those cases that drive you nuts. For condominiums, my area of frustration is special assessments. Those terrible situations where owners have to come up with a huge chunk of cash to rectify a problem that cannot be covered with existing reserve fund capital.

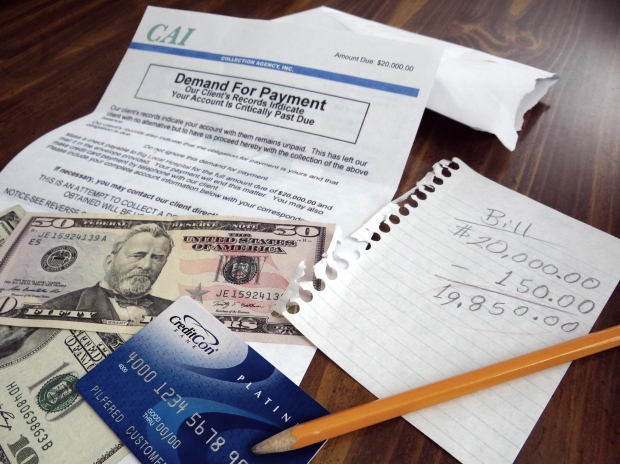

Special assessments are never fun. Directors never want to have to go to their neighbours and say “Hey, I guess we need $20,000 to finish that roofing project. Yes, I do know that it does not impact you directly, but everyone needs to chip in.” People have to delay trips, refinance properties, borrow from families and in some cases, sell the property as they just can’t afford the request being made. There is often that one owner who blames everyone else in the room, and makes a tough situation even more difficult. While sometimes justifiable, in others it is just the inability to come to a realization that they NEED to pay.

The Alberta Court of Queen’s Bench decision of Condominium Corporation No 0213865 v. Uhrik, 2014 ABQB 478 (CanLII), <http://canlii.ca/t/g8r0f> reads like one of those decisions. In this case, there was a problem with the building envelope, and a special assessment of over $87,000 (with a portion refunded later). The defendant, a unit owner, refused to pay because it was a surprise and because he did not have enough notice. He then proceeds to allege negligence and defamation, and sued with a counterclaim for the conduct of the board. The counterclaim was not resolved as part of this motion. The Corporation brings a motion to pursue the judgment based on the special assessment, and all associated interest and legal costs. The court allowed the collection of the judgment to be pursued, as it had a built in delay of 6 months, and the defendant had that time to enforce his claim.

As part of the written decision, Master Robertson, Q.C. made some great statements about the realities of condominium corporations in these situations:

“A Volunteer Board of Directors Manages a Condominium Corporation

[26] Leaky condominiums are an unfortunate fact of modern life. Errors made in the construction of any home, whether a single family dwelling, a semi-detached home, apartment building, a townhouse, or any other form of dwelling structure, often do not manifest themselves for years. Expensive repairs that are required as a home ages are an unpleasant reality for homeowners, whether the home is a condominium unit or not. The nature ofcondominium ownership places the decision to repair, when, and how, in the hands of an elected board of volunteer directors, usually with the support and guidance of a management company, and sometimes their decisions are not happy ones. They must decide what is to be done, what contractor is to do it, and how much money must be raised to make sure the work can be paid for, so builders’liens are not registered against everyone’s unit. They may seek input from the other owners, but the obligation rests with the Board.

[27] In this case, the Board of Directors consisted, I am told, of six members, all of whom are owners of units in the condominium. There are 66 units in the condominium in total. Accordingly, almost 10% of the owners are on the Board of Directors, and in levying the special assessment they were levying a special assessment against themselves, as well as the other 60 owners. The facts are quite clear that this was not a step that was taken to harm the defendant; rather it was a step taken to protect the interests of the defendant as well as the interests of all of the other owners, by making repairs before the building deteriorated beyond the point of repair.

I also enjoyed the commentary about how a condominium corporation is different from a lender as well:

“[58] In respect of the claim for solicitor and client costs, this is expressly provided in the bylaws. It has been claimed from the outset. This is a cooperative-owned building where, he has placed an unfair burden on the remaining owners by forcing the other owners to fund the underlying repair costs while also forcing them to incur legal fees to collect his share of those costs. This is not a financial institution that lent money with the risk of not being able to recover it; it is not a business servicing its customers who chose to take on the risk of credit. The plaintiff here is a collective of the defendant’s neighbours, who are entitled to be treated fairly.

[59] In the circumstances of this case, they are entitled to have solicitor and client costs paid by the defendant in accordance with the terms expressly set out in the bylaws. There is no reason for the exercise of any discretion not to follow their “social contract” as expressed in the bylaws.

Leave a Reply

Want to join the discussion?Feel free to contribute!